What is LASIK?

Laser in situ keratomileusis, or LASIK, is anoutpatient surgical procedure used to treat myopia (nearsightedness), hyperopia (farsightedness) and astigmatism. With LASIK, your ophthalmologist (Eye M.D.) uses a laser to reshape the cornea (the clear covering of the eye) to improve the way the eye focuses light rays onto the retina.

LASIK may decrease your dependence on glasses and contacts or, in some cases, allow you to do without them entirely. According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology, seven out of 10 LASIK patients achieve 20/20 vision, but 20/20 does not always mean perfect vision. If you have LASIK to correct your distance vision, you’ll probably still need reading glasses by around age 45. Therefore, it is important for you to consider the possibility that LASIK may not give you perfect vision.

Am I a good candidate for LASIK?

LASIK is not for everyone, and your ophthalmologist will advise you about certain conditions that may prevent you from being a good candidate for this procedure.

For instance, the ideal candidate for LASIK is over 21 years of age, not pregnant or nursing, and free of any eye disease. You should not have had a change in your eye prescription in the last year and should have a refractive error within the range of correction for LASIK.

You must also be willing to accept the potential risks, complications and side effects associated with LASIK (see “risks” section of this handout). You should discuss these issues with your surgeon, carefully weighing the risks and rewards. If you’re happy wearing contacts or glasses, you may want to forego the surgery.

What happens before surgery?

Your ophthalmologist will perform a thorough eye exam to measure your prescription and check for any abnormalities that might affect the procedure. Your doctor will check your eyes for unusual dryness, which could cause dry eye symptoms postoperatively, or unusually large pupils, which could affect night or low light vision.

How is LASIK done?

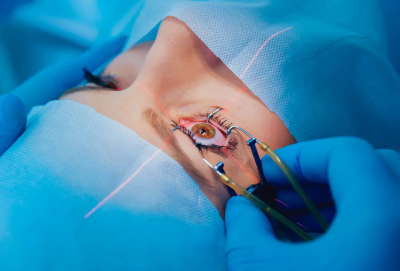

LASIK is performed with the patient reclining under the laser in an outpatient surgical suite. First, the eye is numbed with a few drops of topical anesthetic. These drops may sting. An eyelid holder (called a speculum) is placed between the eyelids to keep them open and prevent you from blinking.

A suction ring placed on the eye lifts and flattens the cornea and helps keep your eye from moving. You may feel pressure from the eyelid holder and suction ring, similar to a finger pressed firmly on your eyelid. From the time the suction ring is put on the eye, until it is removed, vision appears dim or goes black.

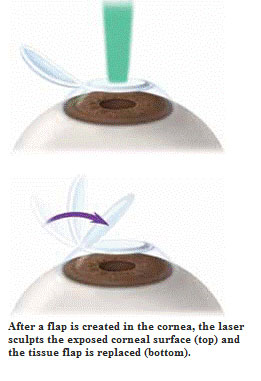

Your ophthalmologist may use an automated microsurgical instrument called a microkeratome to make a flap in your cornea. This device is attached to the suction ring. As the microkeratome blade moves across the cornea, you will hear a buzzing sound. The microkeratome stops at a preset point, far enough from the edge of the cornea to create a hinged flap of paper-thin corneal tissue. The microkeratome and the suction ring are removed from your eye, and the flap is lifted and folded back.

Some ophthalmologists use a specific laser instrument instead of a bladed microkeratome to make the flap in your cornea. With this technique, tiny, quick pulses of laser light are applied to your cornea. Each light pulse passes through the top layers of your cornea and forms a microscopic bubble at a specific depth and position within your cornea. Your Eye M.D. then creates a flap in the cornea by gently separating the tissue where these bubbles have formed. The corneal flap is then folded back.

As the flap is moved aside, your vision gets blurrier. Then a special laser for sculpting the cornea – preprogrammed with measurements customized to your eye – is centered above the eye. In most cases, a pupil tracker will be used to keep the laser centered on your pupil during surgery.